How to Choose the Right Brewery Lawyer

When hiring the right brewery lawyer, you can never go wrong with a thorough vetting process. But what is it, exactly, you should be looking for in selecting a beer attorney for your brewery or business?

Whether you’re operating a brewery, brewpub, bar, or craft beer bottling company, you’re running a business. And like any other business owner out there, you’re likely to run into legal and otherwise issues.

Who is The “Right” Brewery Lawyer

Selecting the right beer attorney for your business shouldn’t be just about the bottom line and the cheapest option — but instead, you should prioritize how the legal team “fits” with your business.

A proper lawyer, when working with your brewery or business, should:

- Be an advocate for your products and business

- Help identify and mitigate potential risks

- Provide sound counsel

- Be considered a trusted source for you and your team

It’s OK to be “Picky” When Choosing a Brewery Attorney

You wouldn’t buy brewing equipment or products from a sales representative that didn’t know their product, would you? The same applies to your business when selecting a beer attorney.

While you could go with cheap options or local attorneys, the best, most efficient option is to go with an attorney specializing in breweries, brew pubs, and other businesses within the industry.

Hire Drumm Law as Your Brewery Lawyer

At Drumm Law, we understand that today’s law firms are inefficient and outdated. That’s why, as a virtual law firm, we’re proud to offer breweries, brew pubs, bars, and others within the industry one-of-a-kind specialized services.

We rely on technology, specialization, quality people, and low overhead to help your brewery or brew pub. Contact us today to learn more about how Drumm Law can help protect your beer trademarks!

Legal Side of Playing Live Music in Your Brewery

So…you own a brewery and want to play music in your taproom. Maybe it’s live concerts with local bands. Maybe you just want the ambiance of having something on in the background day to day. To liberally paraphrase Lesley Gore’s 1963 hit, “It’s my taproom and I’ll jam if I want to!” Unfortunately, this is not a “just press play” situation, so before you start up It’s My Party for your customers, you may want to read on.

Sure, you can listen to whatever tickles your fancy at 8am alone in the brewhouse, but if you are going to be playing music in the presence of patrons, it’s time to add another license to your file.

Really? Another one?

The short answer is… yes. Music is governed under Federal Copyright law. The Copyright Act grants five rights to a copyright owner:

- the right to reproduce the copyrighted work;

- the right to prepare derivative works based upon the work;

- the right to distribute copies of the work to the public;

- the right to perform the copyrighted work publicly; and

- the right to display the copyrighted work publicly

For purposes of this blog, we are focusing on number 4: the “performance” aspect, or, in this case, the performing of copyrighted music at your brewery. Now before you get up on the bar with that microphone…

What is a performance?

According to the US Copyright Act, “to “perform” a work means to recite, render, play, dance, or act it, either directly or by means of any device or process or, in the case of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, to show its images in any sequence or to make the sounds accompanying it audible.”

I’m sorry, what now?

In layman’s terms: a performance is playing music in a public setting (i.e. the taproom).

This means there are two common types of performances you’ll need to consider here: playing pre-recorded music and hosting live music.

Let’s start with playing pre-recorded music. That means Spotify, Pandora, Apple Music, YouTube, your iTunes library on shuffle, vinyl records, CDs, 8-tracks, cassettes, a collage of cell phone videos from that summer you followed Widespread Panic on tour.

Did you say no streaming?

Yep. You probably have your own Spotify or Apple Music account and can Bluetooth or plug into your taproom’s speaker system, right?

Not so fast.

Well what about playing vinyl records or CDs that I own? I paid for them. Why can’t I play them? They are mine.

Negative Ghost Rider, the pattern is full.

While you may own the physical media or pay for the music service, the rights that come with this payment are non-commercial. You can rock out in your car or with your air pods but when you start playing this music for the public, you are now entering the realm of “performance” (air guitar optional).

Streaming services like Spotify, Apple music, Google Play, and Pandora are designed for consumer use and are not fully licensed for commercial purposes. Same goes for that $10 CD you bought. They are for personal use only and do not include a “performance” license, therefore playing them in a commercial setting violates copyright law.

Does that mean we all have to drink our beer in silence?

Not at all. If you want to play music in your taproom, you have three options.

Option 1: obtain a commercial license from one - or multiple - Performing Rights Organizations (PROs) and play music that you legally own (CDs, vinyl records, digital downloads, etc.)

Okay… what is a PRO?

Great question. Musicians, composers, and songwriters create music and own the intellectual property thereof. PROs exist to protect all that IP and ensure that the artists get paid for its use. Musicians can only sign up with one PRO - the three main ones are American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI) and SESAC. These PROs protect the rights of the artists by selling and enforcing licensing of music in establishments like your taproom.

You may have already received a nice letter threatening death and destruction from one or more PRO(s) for not having their yearly license. Something like this:

Dear Brewery Owner,

My name is PERSON and I’m your BMI territory representative.

Every effort has been made to resolve your BMI license amicably, but without success. Because we’ve been contacting you in an attempt to reach a timely and amicable resolve for the music license at your business, BREWERY NAME is currently being considered for Copyright Infringement action. It is important that you understand BMI exists to help businesses and other organizations that use music to comply with US Copyright Law in an easy and cost-effective way.

It is very important that I hear from you today.

The cost of using music without permission can be very high. Each musical composition used without authorization entitles the copyright owners to damages between $750 and $30,000, plus attorney's fees and costs. The amount awarded is at the discretion of the judge, who can grant an award as high as $150,000 per infringement, if the court determines the infringement to have been willful.

Please contact me at your earliest convenience to secure the required copyright permission licensing for your business.

Thank you for your prompt attention,

PERSON

If you decide to go with this option, you will either have to obtain licenses from all three PROs or only play music from the catalogue of the PRO with whom you hold a license. Licensing fees are based on the occupancy of your tap room and can add up in a hurry.

This leads us to the more popular (and cost-effective)

Option 2: sign up for a commercial streaming service that includes the commercial licenses. Think of it as a fancier Spotify. These services run between $25 and $27 a month and include full commercial licensing on a full catalogue of songs, making this option indubitably cheaper than licensing from the PROs. Pandora Business and Sirius XM Business are two popular options.

Don’t like the sound of those numbers? There is one final possibility.

Option 3: play the good ol’ fashioned radio… so long as you meet certain requirements.

If you want to play your favorite local radio station, you must have the “right” size building and the “right” number of speakers. Under the US Copyright Act, a brewery is eligible for the exemption if it either (1) has less than 3,750 gross square feet of space (in measuring the space, the amount of space used for customer parking only is always excludable); or (2) has 3,750 gross square feet of space or more and (2) uses no more than 6 loudspeakers of which not more than 4 loudspeakers are located in any 1 room or adjoining outdoor space.

When considering these options, it may be worthwhile to also look at your event schedule.

What if I have live bands?

As a host of live music, you (the venue) are responsible for the licensing fees of the songs played in your establishment. A Pandora Business or Sirius XM account does not cover (and there is, unfortunately, no equivalent for) live music. You will have to go with a PRO option.

“But hold on,” you say, “I’m not hiring famous bands for my taproom. I only work with local artists. Surely, I don’t need a license for that.”

Well, we hate to disappoint, but even local bands sign up with PROs. The above-listed organizations have no scope requirements when it comes to membership (although SESAC is invitation-only) and even small-time performers wishing to protect their music can apply. The second issue here is that your local band may perform cover songs. PROs cover the songwriter, not the performer, so if you have a completely original set that finishes with Freebird, you’re still looking at a copyright violation.

Therefore, if you want to have live music and do not want to pay for PRO licensing, you’ll have to:

(1.) Have the band grant you a public performance license for its songs and

(2.) Have the band agree to only play their music (no covers). Remember that you (the venue) are ultimately responsible for complying with copyright law and proper licensing so it’s important that they (the band) understand that you are on the hook if they decide to play Freebird after all.

Three PRO licenses for one show? Can I just get one?

Sure. If you don’t want to give up on covers entirely, but don’t want to pony up for all three licenses either, you can settle on just one. You’ll just have to work with the band to select only cover songs licensed by that PRO. Ultimately, the decision of which PRO or PROs to buy licenses from may factor into how frequently you host live music and vice versa.

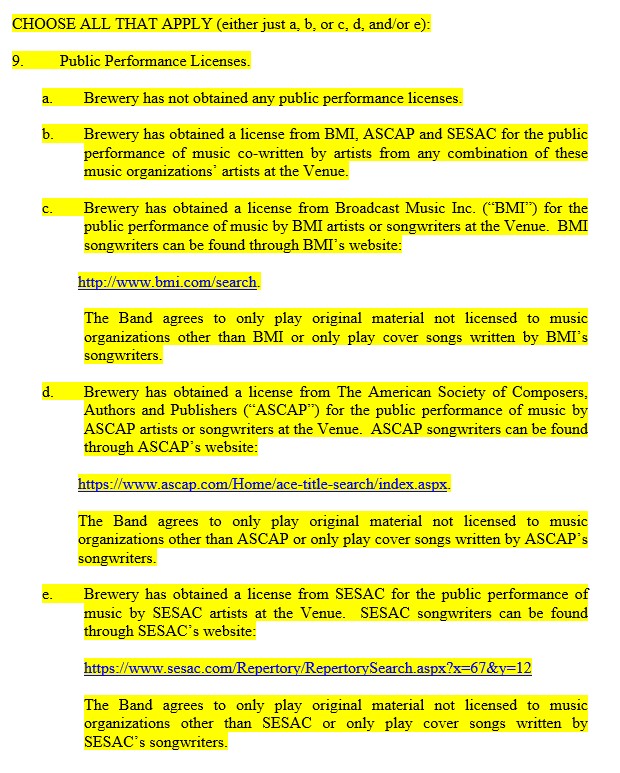

We have a Live Music Agreement template available to breweries at no charge. All you have to do is ask. Our template lets you choose which PRO license you have, if any, and provides links to each PRO database so bands can pre-screen cover songs:

Our agreement also includes a limited public performance license grant for the band’s original material.

Our agreement also includes a limited public performance license grant for the band’s original material.

I haven’t done any of this and it’s been fine so far. What if I keep doing what I’m doing?

Harassment from the PROs. Bad karma. Oh.. and fines exist. Remember the BMI letter above? “Between $750 and $30,000.” Is Freebird really worth $30k?

Questions? Feel free to contact us. We’re happy to discuss your options in more detail and help you figure out the best way for your business to be in compliance.

8 Things to Know Before Signing Beer Distribution Agreement

Beer and Distributors, beer and distributors

They go together like a horse and carriage

This I tell you, brother

You can’t have one without the other

Selecting a Distributor and selecting a spouse have a surprising number of similarities. It can be difficult to find the perfect fit. The relationship will have its ups and downs. And, most importantly, it can be expensive to end the relationship if it is not working out.

If you decide that it’s time to tie the knot, here are few key points to consider before you sign the “Prenuptial Agreement” (a/k/a the Distribution Agreement).

What to Consider Before Signing a Beer Distribution Agreement

1. Know your state’s distribution laws. These laws will override the contract terms so it is important that you know what rights you and your distributor have under the state law.

2. Define your territory carefully and specifically. We recommend that you add the following language to the Territory definition of your Distribution Agreement so that you do not end up in situation where you are required to purchase your own beer back from your distributor to sell it:

The following is excluded from the Territory definition: any physical location of a restaurant, brewery, brewpub or taproom (or similar establishment) owned by Brewery or its affiliate(s)

3. Be specific in the products that will be distributed. Be sure to exclude tap room only releases and beers that are brewed for certain markets (think Colorado Native by Coors-only available in Colorado). Make sure to carve out contract brewed beers and collaboration beers or you may inadvertently be unable to provide contract brewing services or work with other breweries on collaboration beers. We recommend that you add the following language to the Product definition of your Distribution Agreement:

Products shall not include any fermented malt beverage that: (1) is made under a contract brewing agreement for a third party which may be produced by Brewery for sale or distribution under third party brands not associated with Brewery or an affiliate of Brewery; or (2) is designated as a tap-room only (or similar language) release; (3) is a collaboration beer brewed at another brewery and not intend to be distributed by Brewery or (4) is designated for release exclusively outside the Territory.

4. Specify who is financially responsible for out-of-code products. Is the distributor responsible? Do you split the costs? While ideally this would be the distributor’s cost, you have to balance having old product in the marketplace against the disposal expense.

5. Specify who is financially responsible for the marketing the products in the territory. Does the distributor have to purchase tap handles? Do you split the marketing expenses up to a certain amount?

6. Distribution Agreements typically have a net 30 payment terms. As you will have incurred the costs for the products long before the net 30, make sure to include a late fee and interest to encourage your distributor to pay on time. Here is a sample provision:

Distributor will pay Brewery a late fee the lesser of the daily equivalent of: (i) eighteen percent (18%) per year simple interest; or (ii) the highest amount allowed under law, on any overdue amount for each day any amount is past due calculated from the date of the original delivery of the Products and accruing until the past-due amount is paid in full. This provision does not permit or excuse late payments.

7. What’s worse than not being paid on time by your distributor? Having to provide more products while you are not being paid. Be sure to include a provision that allows you to suspend the delivery of products to the distributor if the distributor has a past due balance. Here is a sample provision:

Brewery shall have the right, at its option, to suspend delivery of Products during any time period Distributor is past due on amounts owed to Brewery, effective upon receipt of notice by Distributor.

8. If the Distribution Agreement contains a termination fee to end the distributor relationship, try to specify the exact formula (unless your state law requires “Fair Market Value”). This will let you know if you can afford to end the relationship and will help you in courting new distributors. Formulas typically range from 3 to 5 times the previous year’s gross margin. Avoid having “greater of” provisions which specify a multiple and the fair market value. If the Distribution Agreement has a fair market value clause, this by definition is the fair market value. The “greater of” provision may put you in a situation will you will have to pay more to terminate the Distribution Agreement than is “fair.” Here is a sample provision:

Brewery shall pay to Distributor on the 30th day after the notice a sum equal to three (3) times the gross margin earned by the Distributor from the sale of the Products in the 12 months preceding the month in which the notice is given.

Distribution Agreements, like marriages, typically do not have end dates. Also like marriages, they typically end (at an expense) when one party is unhappy with the other or if someone better comes along. Do your research before making this potential lifelong commitment.

How to Select Your Clothing Trademark

Trademarks are used to identify products. A trademark tells you about the product (usually who made the product and a certain level of quality). In order to file a trademark for clothing, you have to use your trademark to identify the clothing as belonging to the trademarked brand and not as a decoration. Trademarks that are only decorative do not identify and distinguish goods and do not act as a trademark.

A Ford logo can be used to identify a truck. But the same logo on a t-shirt does not identify a certain brand of clothing (for example, quality, country of origin, etc.). Instead, this logo is being used as a decoration to appeal to people that like the Ford brand.

The size, location, and dominance of the proposed trademark are used to determine whether the mark is a trademark or just a decoration.

While no bright-line rule exists for making a determination whether or not a mark will qualify as a trademark, generally a small, neat, and discrete word or design feature is likely to create the commercial impression of a trademark.

The best bet is to put your trademark on a tag on the clothing itself or on a string connected label.

Understanding Beer Distribution Across State Lines

Trademarks, Beer and State Lines

I don’t distribute out of state. Can I still trademark my beer names?

The short answer is YES!

The Lanham Act (also known as the Trademark Act of 1946) is the federal statute that governs trademarks. Generally, the Lanham Act requires that a mark is used in interstate commerce before it may be registered as a federal trademark.

Fortunately, interstate commerce is broadly defined.

Traditionally, interstate commerce has been focused on whether or not goods have physically crossed state lines. Due to the nature of modern commerce, travel, and the expanding reach of the internet, the lines for what is truly “local” has changed over the years.

“Use in Commerce” Within a State

Adidas (the shoe and apparel company) tried to trademark “ADIZERO” for athletic apparel (fun fact-one of the founding brothers of Adidas broke off and formed the shoe company Puma). The Trademark Office blocked this trademark because of a likelihood of confusion with the trademark “ADD A ZERO,” which was a clothing trademark owned by a church in Illinois for its fundraising campaign to encourage its congregants to add a zero to their donations (as in don’t give $10, give $100).

Adidas argued that the church’s marks were not in interstate commerce. The Illinois church defended the alleged non-use in interstate commerce argument by offering evidence that it had sold two hats bearing the contested marks to a parishioner who resided across state lines in Wisconsin. The sale occurred within Illinois, so the church did not rely on a sale made to a customer located across state lines at the time of the purchase. Adidas argued that the sale of two hats were “de minimis,” meaning too trivial or minor to merit consideration for interstate commerce. Adidas won at the trademark court and the decision was appealed.

The Federal Circuit on appeal clarified the broad protection of the Lanham Act and reversed the trademark court holding. The Federal Circuit stated that the Lanham Act defines interstate commerce as all commerce which may lawfully be regulated by Congress.

The Federal Circuit held on appeal that the church’s sale of two hats showed that the marks were used in interstate commerce for Lanham Act purposes. The Federal Circuit Court held that the church was not required to present evidence that its sale of hats actually affected interstate commerce, or even to show that the hats were destined to cross state lines. Rather, the church merely needed to show that its sale activity, even if just local, fell “within a category of conduct that, in the aggregate” could exert a substantial effect on interstate commerce.

Say That Again Please (In English)

Breweries make beer. Beer is offered for sale. Out of state people may purchase said beer at the brewery, restaurants or other locales. These purchases in the aggregate can affect interstate commerce.

Helpful Tips

Because the law (or the courts’ interpretation of the law) can change, here are some practical tips to support that you have interstate commerce beer:

- When you release a new beer, make sure to get it on the worldwide web (whether through your own website or through the various social media channels).

- Encourage your guests to review your beer on the various beer review websites (odds are good you will have plenty of out of state).

Cheers!

How Much Does it Cost to Trademark a Beer or Brewery Name?

Trademark Costs for Beer and Breweries

So you’ve decided to make the leap and apply for a trademark for your beer or your brewery.

You’ve settled on a word, phrase or design that is suitable for trademark, done your clearance search to make sure nobody else is using that mark, and are ready to apply. You go to the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”) and start to look at the long list of fees. What now?

The cost to file a trademark online

The USPTO has a long fee schedule for various types of filings. For new applications, you can file it online using the USPTO’s application website, using the TEAS Plus application, which is simple, quick, and gets your application filed immediately. For a TEAS Plus application the fee is $250 per international class.

Now for the fine print:

The application fee in the U.S. is per international class. What is an international class?

It is a schedule of numbered classes of goods and services in which you classify a trademark. For example, beer would fall into Class 032 for beverages. But you may wish to register a trademark in more than one international class. For example, a brewery may want to register its brewery trademark for beer (Class 032), taproom services (Class 043), and maybe for merchandise, like T-shirts (Class 025). When you file an application for a trademark in multiple international classes, you have to pay the fee for each class applied for. So the brewery example above filed using TEAS Plus would have a filing fee of $750 ($250+$250+$250). That is only the filing fee charged by the USPTO; it does not include attorney’s fees for any assistance in filing by your attorney, or other costs.

In addition to the initial filing of an application for the trademark, you will have to make periodic filings to maintain your trademark. After six years, you must file a renewal filing to demonstrate your continued use of the mark, for example. Or if you filed an intent-to-use application (where you file an application for a trademark before you have actually proceeded to use the mark in commerce), you will have to file a statement of use. These filings vary between $100 and $300.

Other trademark costs you should anticipate are costs to respond to any refusal or opposition to your trademark during the application phase. Your trademark application is examined by an Examiner at the USPTO, who may issue an Office Action stating certain grounds for why your trademark should not be published. You or your attorney will have to respond to such Office Actions, which come with your attorney’s fees and costs. Also, even if your mark is published, another person may oppose the registration and file what is called an opposition (before your mark is registered) or a cancellation (after your mark is registered). Responding to these filings (or if need be, filing your own oppositions and cancellations) come with filing fees of $400 and attorney’s fees and costs, sometimes hefty sums.

Using Names in Beer or Brewery Trademarks

Using Names in Beer or Brewery Trademarks

You have a great idea for a beer concept and want to have a catchy name for the beer or brewery, so you decide to use your old uncle Bob’s name. Can you trademark Bob’s name for your beer or the brewery? It depends.

Can You Trademark a Name?

One of the grounds used by the USPTO for refusal to register a mark is Section 2(c): “Consists of or comprises a name, portrait, or signature identifying a particular living individual except by his written consent, or the name, signature, or portrait of a deceased President of the United States during the life of his widow, if any, except by the written consent of the widow.” So, no President Obama Porter, thank you very much. And no use of Bob’s name, if alive, without his written consent filed with the USPTO.

This is also covered in Section 2(e)(4) under descriptive marks for “merely surnames.” Why the prohibition on “mere surnames” serving as marks? Mostly because it is merely descriptive. “John’s Ale” is as merely descriptive as saying “this is my ale.”

There are five elements used in analyzing whether a mark is “primarily merely a surname” and might be refused as merely descriptive:

- whether the surname is rare (see TMEP §1211.01(a)(v))

- whether the term is the surname of anyone connected with the applicant (see TMEP §1211.02(b)(iv))

- whether the term has any recognized meaning other than as a surname (see TMEP §§1211.01(a)–1211.01(a)(vii))

- whether it has the “structure and pronunciation” of a surname (see TMEP §1211.01(a)(vi))

- whether the stylization of lettering is distinctive enough to create a separate commercial impression (see TMEP §1211.01(b)(ii)).

Where the mark is in standard characters, it is unnecessary to consider the fifth factor. This determination is made from the point of view of American buyers familiar with the foreign language. For example, FIORE – Italian for flower – was held to not be primarily a surname since American consumers would not generally recognize the word in its English translation. So, the more obscure the foreign surname, the more likely the name may pass muster and be registered.

Another consideration in using a name of a person, even a non-living person, is whether the use would impinge on any rights of publicity in the name of a person. Many states passed “celebrity name” rights statutes in the post-World War Two era, which protect the rights of the descendants of famous persons to the use of their ancestor’s names for publicity purposes. Most of those statutes, however, have a time limitation. For example, Oklahoma’s post-mortem celebrity right of publicity statute does not apply to persons who died before January 1, 1936. There are also common-law rights in persons’ names and personas, which vary widely by state.

It would be advisable to always consult with an attorney before attempting to use a name of a person- living or dead – for a trademark for your brewery and beers.

Trademark, Copyright or Patent: Which is Right For You?

Trademark, Copyright or Patent – Which is right for your business?

There is often a great deal of confusion over whether a trademark, copyright or patent is the appropriate intellectual property solution. Whereas copyrights and patents protect original creative works, trademarks protect business branding and good will in the marketplace.

Copyrights

Copyrights are granted under federal law for original creative works in just about any medium imaginable – writings like books, music, even statues.

Patents

Patents are protections under federal law for original functional creative works, i.e, inventions.

Patents protect things like new kinds of machines, chemical and other processes, and new ways of doing things in non-obvious ways.

Both patent and copyright therefore are federal protections for new, original, creative works and protect the author’s or inventor’s rights to use, distribute and profit from the creative work.

Trademarks

Trademarks, however, are a different animal. As the U.S. Supreme Court has noted in the Trademark Cases, “neither originality, invention, discovery, science, nor art is in any way essential” to trademark rights. Trademarks do not have to be new, creative, or original in any way, other than not having someone else already using it. Trademarks can be as boring and unoriginal as “ACME Tool Company.”

Instead, trademarks protect the words or symbols used by businesses and individuals in distinguishing their goods and services sold in commerce from the goods and services sold by others. Trademarks have been considered as a device to protect the goodwill or reputation of businesses who have spent time and money in building their brand recognition with consumers in the marketplace. Trademark is not a property right in the word – one does not “own” the words or symbols constituting the mark to the exclusion of others. Trademark only protects the registered owner from others using the mark on similar goods or services, impinging on the goodwill and reputation of the registered owner and causing confusion in the marketplace. This distinction is reflected in the definition of trademark in federal law:

- “The term “trademark” includes any word, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof… used by a person… to identify and distinguish his or her goods, including a unique product, from those manufactured or sold by others and to indicate the source of the goods, even if that source is unknown.

15 U.S.C. § 1127.

*Trademarks are a valuable component of every business marketing plan. If you have any doubts about whether you need a trademark, copyright, or patent, the attorneys at Drumm Law can be of assistance.*